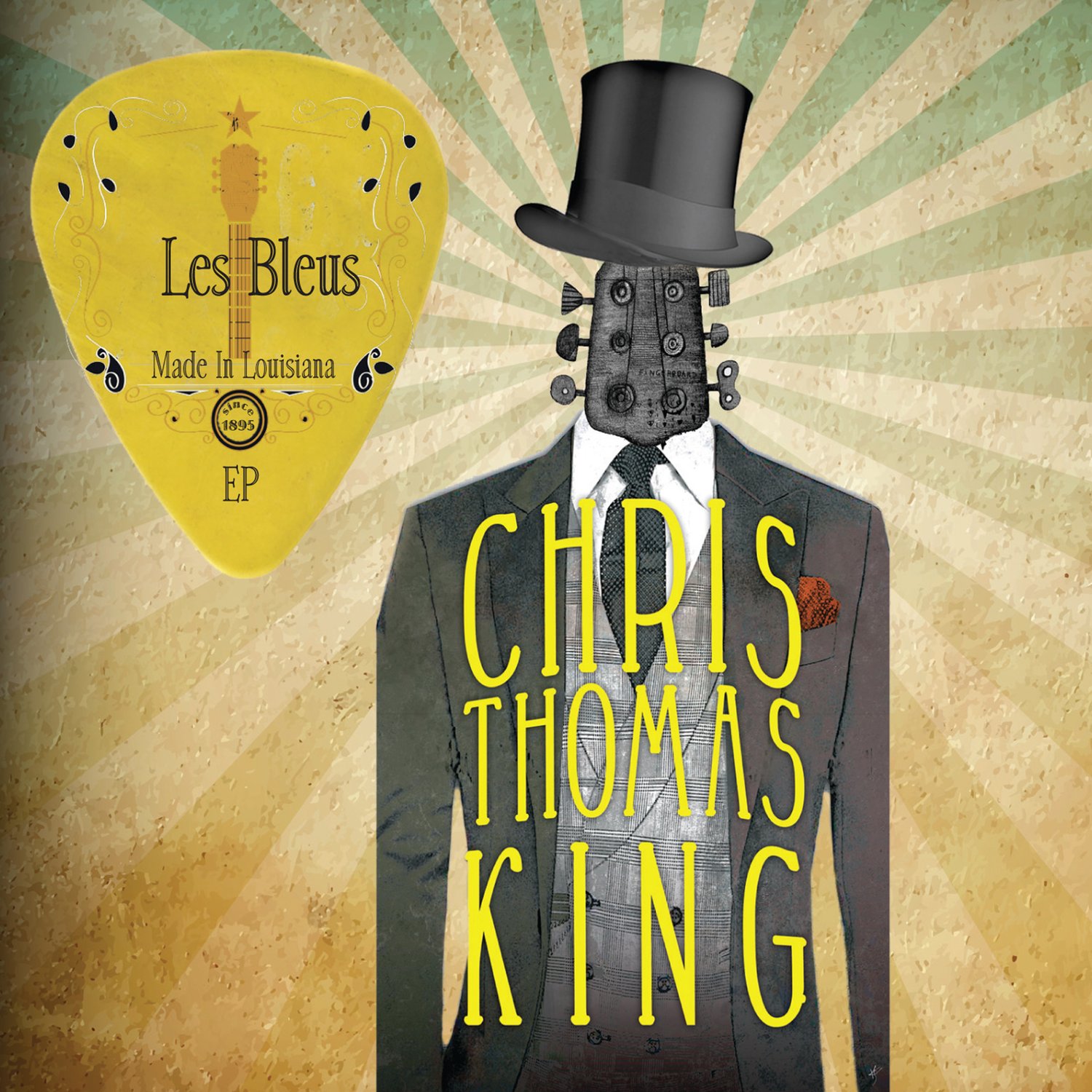

Chris Thomas King, a son of Tabby's Blues Box, talks about where the music came from

The blues-based guitarist and singer argues that the blues originated in Louisiana, not Mississippi. He'll play two shows at Snug Harbor this weekend

Nov 2, 2023

Chris Thomas King is a blues-based guitarist, a singer and an actor who appeared alongside George Clooney in “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” and Jamie Foxx in “Ray.”

In 2021, he added another line to his resume: author. His “The Blues: the Authentic Narrative of My Music and Culture” (Chicago Review Press) is part memoir, part meticulously researched historical argument that the blues originated in Louisiana, not Mississippi.

King's new, digital album is called “Big Grey Sky.” He’ll play two sets at Snug Harbor Jazz Bistro on Friday at 7:30 p.m. and 9:30 p.m., backed by bassist Justin Davi and drummer Darryl White. Tickets are $30.

The following interview, edited for clarity and length, is excerpted from a recent episode of “Let’s Talk with Keith Spera” on WLAE-TV.

Why are you trying to take the blues away from Mississippi?

I’ve done so much over the years for Mississippi. Documentaries, movies, I was instrumental in the research to establish the B.B. King Museum in his hometown (Indianola) and raise money for that. But I felt, at a certain point, what have I done for my home state?

I began writing a book that would be a memoir about growing up in my dad’s juke joint (in Baton Rouge), Tabby’s Blues Box. But I realized that the blues didn’t have a history. I shelved the book I thought I was writing and delved into all these myths and legends. Did Robert Johnson really sell his soul at the crossroads in the Delta?

I found that, in northern Mississippi where they say the blues began, African Americans weren’t even there. It was Native American land until after the Civil War. Those plantations in the Delta are 20th-century plantations.

Long story short, blues really developed here in Louisiana in the 1890s.

Your book has a heckuva lot of footnotes.

Over 350 notes, so this is not just my opinion. The definition of the blues that Mississippi has is not the same definition as Louisiana. The definition in Louisiana has to do with “blue” laws, where they had no gambling on Sunday, no dancing, no buying wine, no “blue” activity, no “blue” language. “The blues” is based on a French Creole word.

When the musicians left New Orleans after Storyville (was shut down in the early 1900s) and went to Chicago or Harlem and called their music “Basin Street Blues” or whatever, people up north made a false translation. In their definition, in the Anglo language, “the blues” means down in the dumps, depressed.

But we don’t do that even at funerals. Even on our most religious holiday, it’s OK to drink wine and dance and have the music going all night. That’s our culture.

So we have to tell our own unique story, hold onto our own definitions and not let Mississippi or northeastern scholars define our culture. Our culture is totally different from the other 49 states. It’s called gumbo — it’s not seafood soup.

The book is partly your personal history. You started playing in your father’s band as a child.

There are some musicians who are older than I am and still working in this genre, but my career dates back further than a lot of these folks. I made my first trip to Europe playing the blues in like 1981.

The unique thing about me, and what drove me to want to do this research, is that I was brought into the business not as a commercial artist. I was brought in by folklorists. The Smithsonian Institution “discovered” me.

Folklorists would go out to prisons and find some primitive version of Black music and record that. It wasn’t meant for MTV or “Soul Train.” It was meant for museums and cultural programs. They were into primitivism of Black music.

I was the last in a long line of musicians who were brought into that world. And it was a crazy world, man. I’m trying to get to “Soul Train,” and y’all trying to take me up to the Smithsonian and display me like I’m some kind of artifact! I had to find a way out of that.

This book was a journey to find out who I am. Because it never made sense to me, the way the blues was framed as being a primitive music. I’m supposed to be a primitive musician? Just by writing a book, I think I’ve proved I’m not illiterate.

Getting into Hollywood helped me find a little elbow room to just be an artist, as opposed to trying to live up to those false narratives.

You experimented with hip-hop in an effort to be contemporary and successful. But the irony of your career is that what brought you the most fame was playing traditional acoustic blues in “O Brother, Where Art Thou?,” which is set in Mississippi during the Great Depression. The soundtrack sold millions of copies and won the 2002 Grammy for Album of the Year. The subsequent concert film “Down From the Mountain,” its soundtrack and tour also did well.

The “Down from the Mountain” album sold a million copies. I wrote a song on it called “John Law Burned Down the Liquor Sto’,” which a lot of bluegrass bands still do. It brought me acclaim and a new audience and helped me transcend this narrow blues audience that I was locked into.

If I wanted to do hip-hop blues, which a lot of people frowned upon, or bring deejays into it. ... breaking all the rules is fun. People that I admire, like Miles Davis, don’t let people define you. You’re the artist. You’re painting that picture. You have to go out on a limb, because that’s where the fruit is. That’s where you’re going to get the good stuff.

“Big Grey Sky,” your new, digital album, is the first of a trilogy.

I have a lot of music that I’ve recorded. I’m still in Prairieville (King moved out of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina), which is probably why I can write books and do other things. I don’t have a lot of distractions.

I have about 35 songs that I’m ready to release. The blues audience, you’ve got to spoon feed them a little bit. I’d blow their minds if I’d give them the whole thing.

On “O Brother,” I played acoustic guitar. People thought, “He’s an acoustic guitar guy.” But I used to have dreadlocks down my back.

You cut them for the “O Brother” movie.

I did. That was part of getting the gig. The dreadlocks, an electric guitar and Marshall amps, that was my thing. I was a heavy blues rocker. (The movie) changed my image.

“Big Grey Sky” has me getting back to the electric guitar and some standard, 12-bar blues things to remind people this is the essence of what I express as a blues artist. The next album will feature me doing early classic New Orleans music by Lonnie Johnson and King Oliver.

What's the state of the blues?

People say the blues is dying out. What was dying out was the sharecropper and the guy who picked cotton. If you didn’t pick cotton, then you’re not a “real” blues musician.

That’s why New Orleans has always been eliminated from the story. Lonnie Johnson, who really is the father of the blues guitar and is from New Orleans, never picked cotton. He was an urban, bohemian type of guy. He’s the one who inspired Robert Johnson and Buddy Guy and B.B. King and Eric Clapton. It all starts with Lonnie Johnson.

Sometimes my music has been ahead of the times or behind the times. But I think the book came at the right time.

“Let’s Talk with Keith Spera” is a partnership between WLAE-TV and The Times-Picayune | NOLA.com. It airs Thursdays at 7:30 p.m., with repeats on Sundays at 9:30 p.m. (Channel 32 in New Orleans, COX Channel 14 and 1014, Spectrum Channel 11 and 711 and AT&T and DISH Channel 32). Episodes are also available on the WLAE YouTube channel.